Blog: TSPDT6 & Note on Xenobuddhism

On Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) Antonin Artaud stated that the film was meant to “reveal Joan as the victim of one of the most terrible of all perversions: the perversion of a divine principle in its passage through the minds of men, whether they be Church, Government or what you will.”

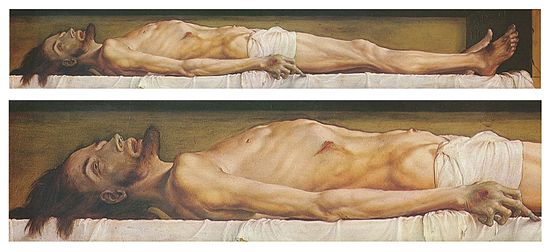

And in my opinion it does just that, and it goes about it in no overly complex way, there’s little in the way of sophistication or creative temperament, just a sublime (and I do not use that word lightly) performance by Renée Falconetti, a minimal set and a focused camera technique. The film is an exercise in compressed spirituality, wherein each time the camera is focused upon Joan of Arc’s face one gets the feeling of a real, visceral belief in God, in saviour. The feeling is akin to reading the works of Lovecraft, where that which is nowadays often accused of being a fiction is brought to life by those who have firsthand experience of the/an Outside, whether it’s Arc’s God or Lovecraft’s Occult, both are read as if that which is usually questioned is taken as reality, fictions become fact. The use of light and dark could be said to be kitsch, potentially obvious, yet it stands entirely true for its purpose as that which reveals the good from the bad. There’s very clear inspiration here for countless films to come, the use of harsh close-ups, little-to-no-makeup, angles utilized as status signifiers, yet it is unarguable that what stands out is Falconetti’s ability to make even the most staunch non-believer question their heart, even for just a second. In Dostoyevsky’s 1869 novel The Idiot, the character Prince Myshkin, having viewed the The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (below) in the home of Rogozhin, declares that it has the power to make the viewer lose his faith. Well I claim the reverse is true for Renée Falconetti’s performance as Joan of Arc.

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb – Hans Holbein the Younger, 1520-22

Renée Falconetti as Joan of Arc.

Now, onto the rest. The Wedding March and Pandora’s Box (1928) are both difficult to find, in fact, now I’ve left the era of really early stuff I imagine I’m going to be confronted with both rare and protected films. People on Sunday (1929) was about as enjoyable as it sounds, don’t bother. The Man with the Movie Camera (1929) I generally thought of as pretty convoluted and hammed up, this is usually the case with a lot of French stuff to be honest, they try just that little bit too hard and what could have been an interesting experiment/experience trails into a nonsensical reference only a few people will get. The Blood of the Poet (1930) was another non-find. L’Age D’or (1930) supposed to be one of Bunuel’s greats, hell I couldn’t draw much from it. Earth (1930) by Dovzhenko was a film I was looking forward to, Tarkovsky lists it as one of his favourites, stating that Dovzhenko understood how to create simple cinema, truly minimal film, there’s a fine line and I guess once again my temperament fell onto the wrong side of it, alas…I was unimpressed. Hell, I never said I was going to glorify the whole list, hopefully by the end of this I can give you the films from this 1000 that’ll actually interest your 21st-century addled brains.

Edward Van Sloan: [Introduction to the film] How do you do? Mr. Carl Laemmle feels it would be a little unkind to present this picture without just a word of friendly warning. We’re about to unfold the story of Frankenstein, a man of science who sought to create a man after his own image without reckoning upon God. It is one of the strangest tales ever told. It deals with the two great mysteries of creation: life and death. I think it will thrill you. It may shock you. It might even horrify you. So if any of you feel that you do not care to subject your nerves to such a strain, now is your chance to, uh… Well, we’ve warned you.

James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) I’m guessing is as clear cut as Frankenstein films are going to come, oh, and also it’s our first ‘talkie’, there’s dialogue again so these might just get a little longer. This is a very clear cut horror which arguably spent a little bit too much time in the editing room (unless there’s a story there I’m missing out on), it’s often jarring how quickly we’re moved along to the next clear piece of narrative, almost…mechanical. I jest, with a remaster this could quite easily sit alongside contemporary horror films as an example of how well a written work can be turned into film.

Extras:

Note on Xenobuddhism:

XENOBUDDHISM BEGINS WITH XENO by XENOBUDDHISM

‘Land goes on, gets blunt, boils this shit down:

“Xenobuddhism- the illusion of the substantial self isn’t dispelled by argument, and for most people it won’t be meditation or some of kind of psychological discipline that does it – getting copied, downloading thoughts, splitting/merging consciousness – that stuff will really have an impact and yes, it will be difficult to ignore”

Xenobuddhism is neither Buddhism nor accelerationism nor transhumanism. It is born from their convergence. It’s Buddhism once exposed to the mutagen, the black liquid. It’s the technocommercialist takeover of dharma in the realisation that techniques for realisation have outpaced humanity. Capital begins rerouting human agencies, demonstrating emptiness as the immanent engine of history. Buddhist modernism sought to update the former based on the latter; Xenobuddhism is dharma expounded by modernity itself. Xenobuddhism is unconditional accelerationism apprehended in the guise of a religion. The self illusion – the heart of the human security system – will be vaporized, and the species with it. Enlightenment and Enlightenment colliding. Whoever says it’s a dystopian picture really hasn’t been paying attention to history thus far.’

An intriguing read by Xenobuddism to be sure, I quarrel with the idea of the human-security-system here in relation to Buddhism. Yet it reads as if there were a mirror (=human-security-system), read the story of The Sixth Patriach Hui Neng. So here I would say that Xenobuddism makes the mistake of the first poem:

The body is the wisdom-tree,

The Mind is a bright mirror in a stand;

Take care to wipe it all the time,

And allow no dust to cling.

The human-security-system here acting as the mirror, yet the proposition that there is a mirror (within Buddhism) is wrong:

Fundamentally no wisdom-tree exists,

Nor the stand of a mirror bright.

Since all is empty from the beginning,

Where can the dust alight.

Whether or not this implies that the Buddhist mind falls quite sharply into unconditional ways of ‘thinking’ would require further investigation. There’s no mirror for dust to collect upon, there’s no human-security-system for the black liquid to collect upon, so it’s washed directly through you, potentially into you, there’s little time for transition here it seems. The substantial self (as Land puts it) in Buddhist terms never was, it was created after and so it’s more a case of realization of negation, as opposed to dispelling an attached psychological reality.

[…] continues his film review series with TSPDT6, focusing on two absolute classics: Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc and Whale’s […]